This is the reading notes for ‘Secrets of the Javascript Ninja, 2nd Edition’, an amazing book explaining the Javascript basic ideas.

Basic understanding of closure

Simply put, closure allows a function to access and manipulate variables that are external to that function.

1

2

3

4

5

var outervalue = 'ninja';

function outerFunction() {

console.log(outervale);

}

outerFunction();

For example, in this code example, we can see that the outerFunction can see the outervalue which is not defined in it. This is a simple closure.

Then we can have a look at a more complicated example.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

var outerValue = "samural";

var later;

function outerFunction() {

var innerValue = "ninja";

function innerFunction() {

console.log(innerValue);

console.log(outerValue);

}

later = innerFunction;

}

outerFunction();

later();

When the later function is executed, the scope inside the outerFunction is long gone, but we can still get the innerValue and outerValue - When we declare innerFunction in the outerFunction, not only is the function declaration defined, but a closure is created that encompasses the function definition as well as all the variables in scope at the point of function defition.

How does Javascript achieve this, we can have a look at the “Execution Context” firstly.

Tracking code execution with execution contexts

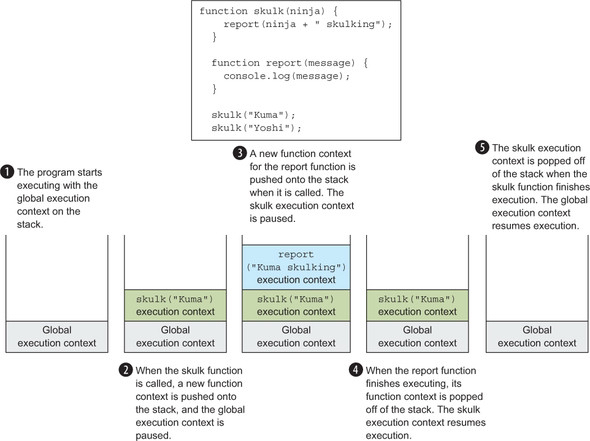

How does JavaScript rack the all the executing functions and return positions?

There are 2 main types of JavaScript code:

- global code, outside all functions

- function code, contained in functions

So we have 2 types of execution contxts:

- global execution context - created when JavaScript program starts

- function execution context - created when each function invocation

Since JavaScript is based on a single-threaded execution model, it uses a stack to store the current executing context and the ones that are waiting.

Below is the execution context stack for a simple code example.

Besides keeping track of the position in the application execution, the execution stack is vital in identifier resolution, the process of fuguring out which variable a certain identifier refers to.

The execution context does this via the lexical environment (also known as scope)

Lexical environments

Lexical environments can track the mapping from indentifiers to specific variables.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

var ninja = "ninja";

function skulk() {

var action = "skulking";

function report() {

var reportNum = 3;

for (var i = 0; i < reportNum; i++) {

console.log(ninja + " " + action + " " + i);

}

}

}

- the for loop is nested within the report function

- the report function is nested within the skulk function

- the skulk function is nested within global code

Each of these code structures gets its own lexical environment every time the code is evaluated. For example, every time the skulk function is called, a new lexical environment for it is created.

The important thing is - an inner code structure has access to the variables defined in outer code structure.

How does JavaScript achieve this? In addition to keep tracking of local variables, function declarations and function parameters of a function, it also keep tracking of its outer lexical environment.

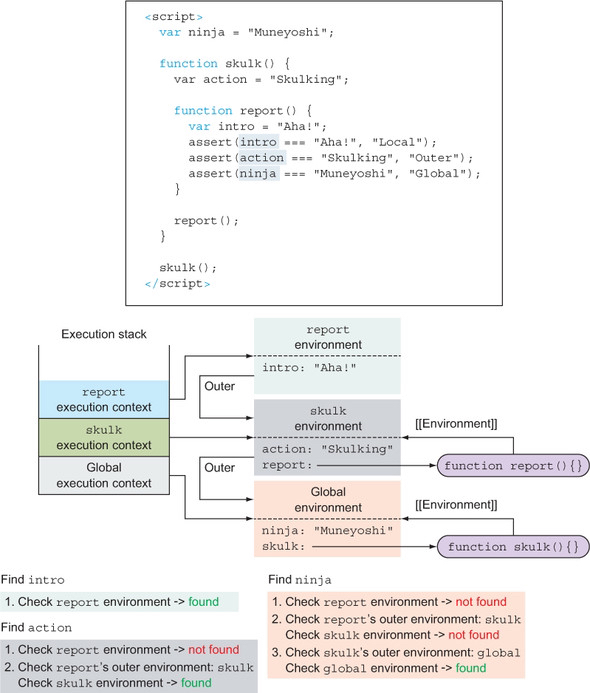

Below figure shows a detailed stack and environment when the skulk function is called.

From the figure, we can see that each execution context has a lexical environment assiociated with it. (Global execution context is associated with global environment, skulk execution context is associated with its own lexical environment, …)

Each lexical environment contains mapping for all identifiers (like ninja and skulk in global environment) defined directly in the context.

Each function contains reference to the outer environment, in which the function was created. This reference is stored in the function’s [[Environment]] property.

Different lexical environments

For the var variable definition, it doesn’t have block environment, the variable is defined in the closest function or global lexical environment.

For the const and let, they will be defined in the closest block environment if exists.

Register variables in lexical environments

1

2

3

4

5

const first = "first";

check(first);

function check(ronin) {

console.log(ronin)

}

In this case, we can see that we call function check() before its declaration, but it still works. This is related to how javascript execution phases.

The execution of javascript contains two phases.

- creation phase - in this phase, the code isn’t executed, javascript engine visits and registers declared variables and functions within the current lexical environment

- execution phase - execute the code

The creation phase

Depends on different environment, the behavior is different. The process is as follows:

- If we are creating a function environment, create arguments identifier, function parameters and arguments values

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

{ arguments: [ 0: param1, 1: param2 ], param1: v1, param2: v2 }

- If we are creating a global or function environment, scan current code for function declarations (not the function expressions or arrow functions).

1

func1: reference to func1

- Scan current code for variable declarations.

- In function and global environments, all variables declared with the keyword var and defined in outer functions, and all variables declared with the keywords let and const defined outside other functions and blocks are found.

- In block environments, the code is scanned only for variables declared with let and const.

For the discovered variables, if the identifier doesn’t exist in the environment, the identifier is registered and its value initialzied with undefined. But if the identifier exisits, it’s left with its value?

Code examples

example 1 - access function before its declaration

1

2

3

4

5

6

console.log(fun); // f fun()

console.log(myFunExpr); // undefined

console.log(myArrowFun); // undefined

function fun(){}

var myFunExpr = function(){};

var myArrowFun = (x) => x;

In this case, function fun() is a function declaration, so the reference is binded on the identifier in the creation phase. And when the exectuion happens, the value exists already.

However, for the function expression and arrow function, during the creation phase, they only have variable registered, but the value is undefined.

example 2 - function overriding

1

2

3

4

console.log(fun) // f fun(){}

fun = 3

function fun() {}

console.log(fun) // 3

In this case, during the creation phase, fun is assigned with function reference. So when the js code execute really, the first line still get fun as the function reference;

while we meet 2nd line, the number ‘3’ is assigned to the fun identifier, in other words, the fun identifier is overriden with number ‘3’.

Explore closure

Mimick private variables with clousres

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

function Ninja() {

var feints = 0

this.getFeints = function() {

return feints;

}

this.feint = function() {

feints ++;

}

}

ninja1 = new Ninja();

ninja1.feint();

console.log(ninja1.getFeints());

ninja2 = new Ninja();

console.log(ninja2.getFeints())

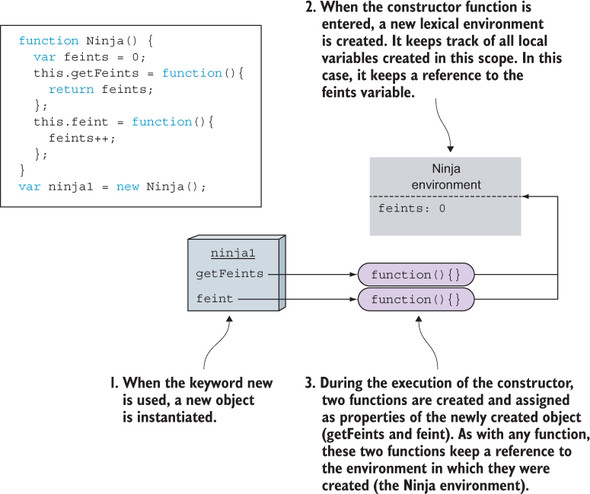

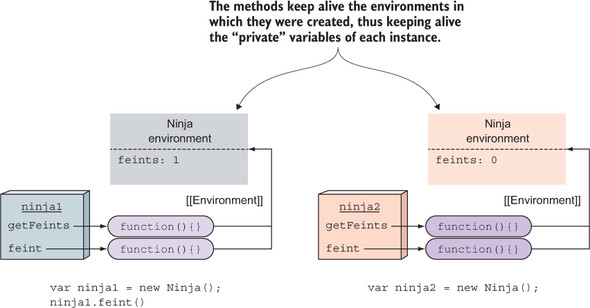

For the 1st Ninja object ninja1, the state is shown in figure below.

When we meet keyword new, the constructor function is invoked, a new object is created, and a new lexical environment is created. And the functions in that object keep reference to where they were created - in this case, both getFeints and feint keep reference to the Ninja environment, where they were created.

When we create another Ninja object, ninja2, the whole process ia the same.

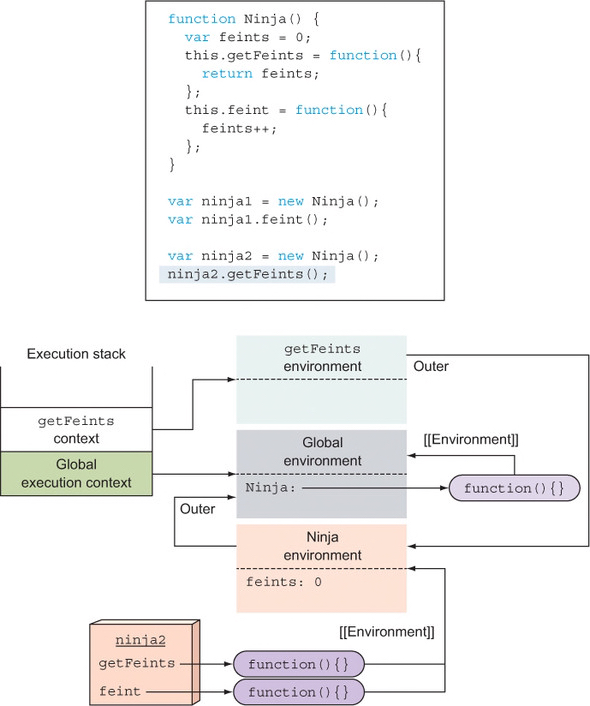

When calling getFeints() method on ninja2, the process looks like below:

When the getFeints() method is called, a new execution context for getFeints() is created and pushed into the execution context stack, and a new lexical environment is created. If getFeints() has it’s own parameter or variables, they will be included during the creation phase. In addition, the getFeints() lexical environment also gets the environment in which it was created - the Ninja environment.

When trying to get the feints variable, firstly, the current environment is consulted. Because we haven’t declared any variables in the getFeints() function, this lexical environment is empty and our target feints won’t be found there. Next, the search continues on the outer environment - the Ninja environment, and we find our target.

callback

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

function animateIt(elementId) {

var elem = document.getElementById(elementId);

var tick = 0

var timer = setInterval(function() {

if (tick < 100) {

console.log(tick);

tick ++;

} else {

clearInterval(timer);

console.log(tick);

console.log(elem);

console.log(timer);

}

}, 10)

}

animateIt("box1");

animateIt("box2");

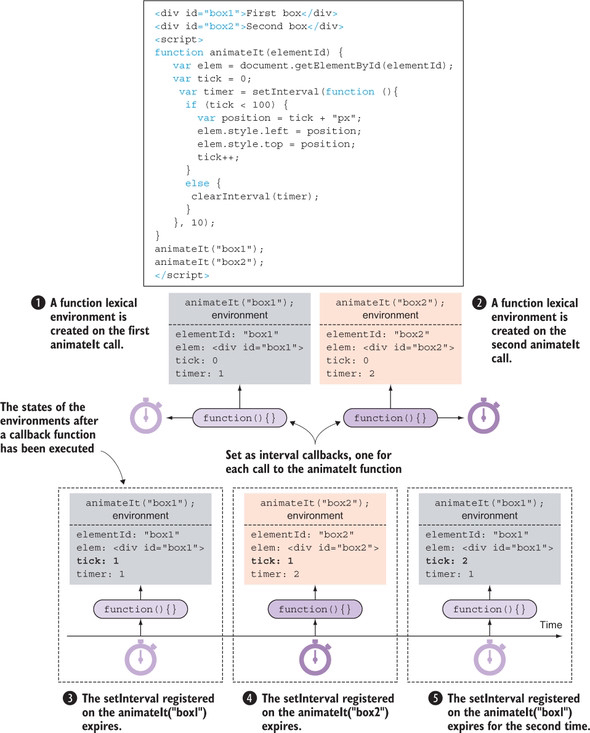

As we can see, in the callback anonymous function, we can access tick, elem, timer; and if we call animateIt() two times, each will mantain its onw variables.

More detailed process: